Galleria Continua

Galleria Continua

Via del Castello 11, San Gimignano

https://galleriacontinua.com

28 September 2019 – 6 January 2020

The solo exhibition “Paradise Lost” by Moataz Nasr, curated by Simon Njami carries us into an oriental world in a transition stage between tradition and modernity. Composed by oeuvres in different media, it shows the large range of Nasr’s creations. Commencing with drawing and sculpture, the show presents also extensive installations, photography and finally video.

Plunging into an oriental world

Entering the venue, the visitor is welcomed by an architectural sculpture of the Barzakh cycle: a tunnel like structure. Framed by abstracted flower mosaics, the two openings are in form of an archway and allow a glance into a seemingly endless space. Accompanied is this chamber of passage by a series of coloured glass figures, reminding the central dome of a mosque. After this announcement of an oriental world, it is recommended not to continue straight away, but to take the detour through the small side rooms.

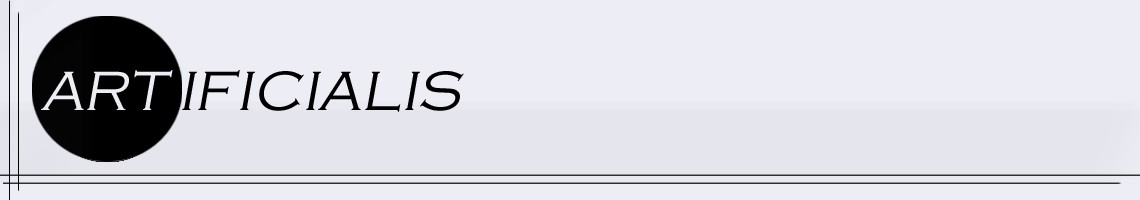

On view is a series of drawings, a little bit like a comic strip with subtitles in Arabic. Still, the non-Arabic speakers could discover a kind of story. However, the story remains a bit concealed, even if it becomes clear that the featured story is located somewhere in the Orient and a young woman is the main actor. Only single hints indicate a temporal setting in the present. Otherwise, the story could take place even in biblical times. The architectural frame underlines the uncertainty: several small rooms meander one after the other, like the narrow streets of a historic medina somewhere in northern Africa. Coming out of this maze-like area, one enters a crepuscular compartment with an oversized chain of lights in the centre. For “Petro Beads” Moataz Nasr has perforated and painted gas containers and strung them like precious pearls. These lights remind traditional metal lamps from North Africa, even though they are a product of recycling. They refer to ancient artisan practice and contemporary habit.

Coming out of this maze-like area, one enters a crepuscular compartment with an oversized chain of lights in the centre. For “Petro Beads” Moataz Nasr has perforated and painted gas containers and strung them like precious pearls. These lights remind traditional metal lamps from North Africa, even though they are a product of recycling. They refer to ancient artisan practice and contemporary habit.

Crossings, Transitions and Transformations

Continuing, one enters the central exhibition room: the wonderful projection hall of the ancient cinema of San Gimignano. A short glance into the audience reveals a monumental sculpture, once again, made out of gas bottles. Nevertheless, before descending there, we stay a while in the area of the former loges. There are three large-size photos, depicting auctions of women. In two of them, the auctioneers are wearing antique himation, while the bidders are clothed rather contemporary. Whereas the women are mostly undressed and they are evidently ashamed. In these photos, the artist reinterprets paintings by Jean-Léon Gérôme from the second half of the 19th century. With his style of the academic realism, the French artist displayed the current scientific state of knowledge about antiquity. Once again, tradition and modernity meet. The paintings are transferred into a contemporary medium: photography. Moreover, Nasr changes the perspective: while Gérôme displayed the European idea of oriental behaviour, the Egypt artist looks at European art history from his position.

Continuing, one enters the central exhibition room: the wonderful projection hall of the ancient cinema of San Gimignano. A short glance into the audience reveals a monumental sculpture, once again, made out of gas bottles. Nevertheless, before descending there, we stay a while in the area of the former loges. There are three large-size photos, depicting auctions of women. In two of them, the auctioneers are wearing antique himation, while the bidders are clothed rather contemporary. Whereas the women are mostly undressed and they are evidently ashamed. In these photos, the artist reinterprets paintings by Jean-Léon Gérôme from the second half of the 19th century. With his style of the academic realism, the French artist displayed the current scientific state of knowledge about antiquity. Once again, tradition and modernity meet. The paintings are transferred into a contemporary medium: photography. Moreover, Nasr changes the perspective: while Gérôme displayed the European idea of oriental behaviour, the Egypt artist looks at European art history from his position.

The Mountain of Fear

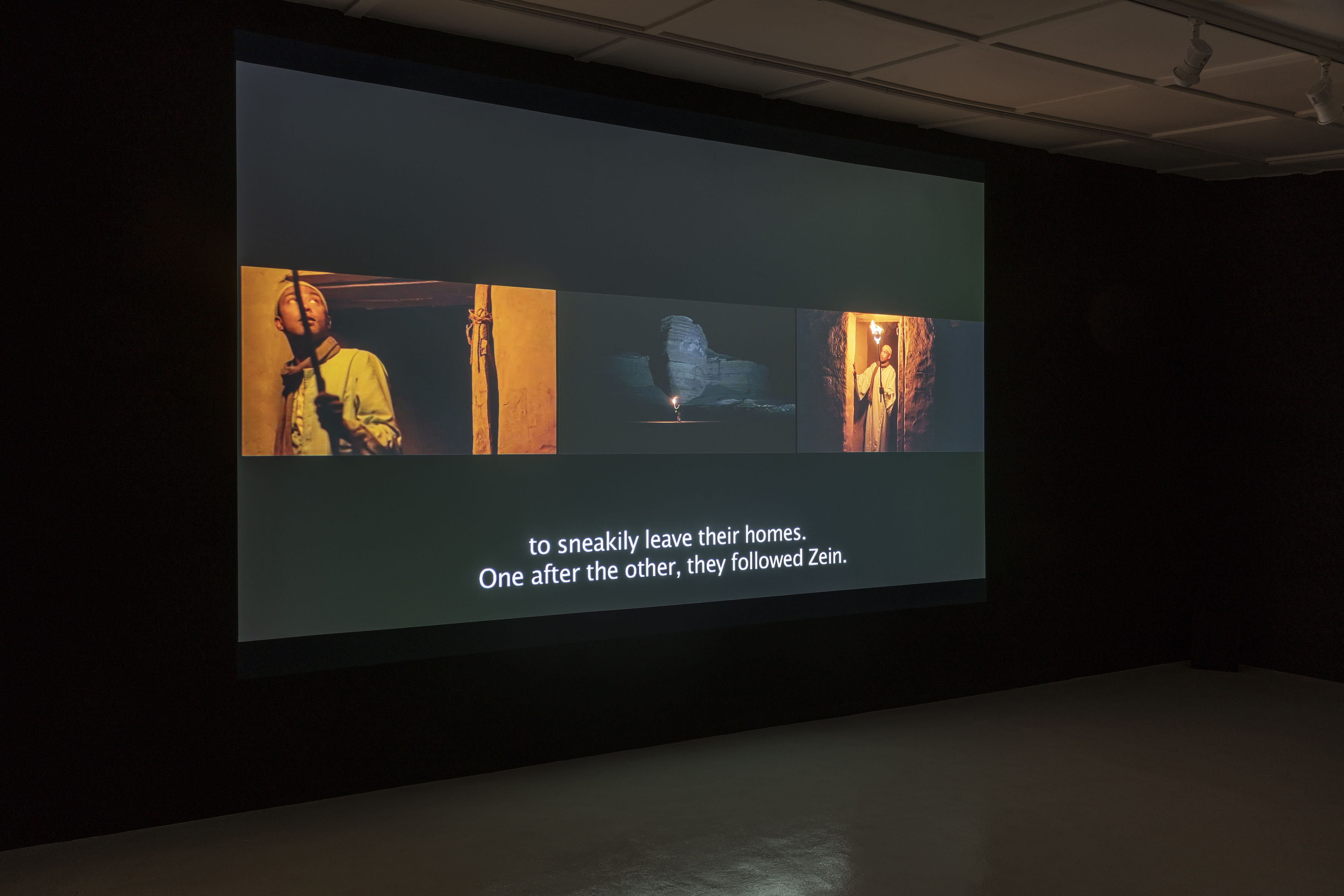

Finally, there is the video installation “The Mountain”, which is pervaded by many of the before seen motives and additionally emphasises the feeling of fear. Presented as five-screen projection in the context of an immersive, multi-sensory experience in the Egyptian pavilion of the 2017 Venice Biennale, the video carries us ultimately to the artist home country. By the style and the images, “The Mountain” is telling a traditional story, a fable as older people might tell in certain circumstances. However, the medium is highly contemporary, a short narrative film.

Finally, there is the video installation “The Mountain”, which is pervaded by many of the before seen motives and additionally emphasises the feeling of fear. Presented as five-screen projection in the context of an immersive, multi-sensory experience in the Egyptian pavilion of the 2017 Venice Biennale, the video carries us ultimately to the artist home country. By the style and the images, “The Mountain” is telling a traditional story, a fable as older people might tell in certain circumstances. However, the medium is highly contemporary, a short narrative film.

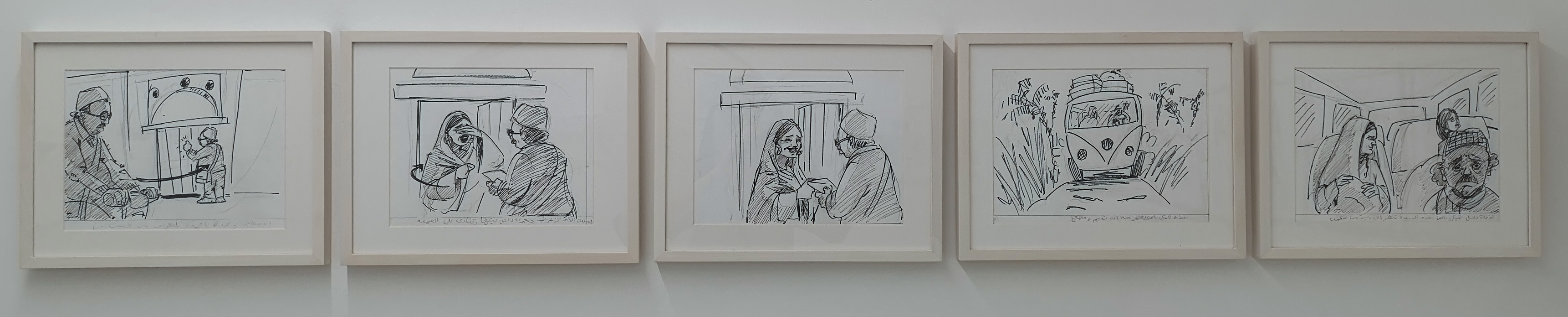

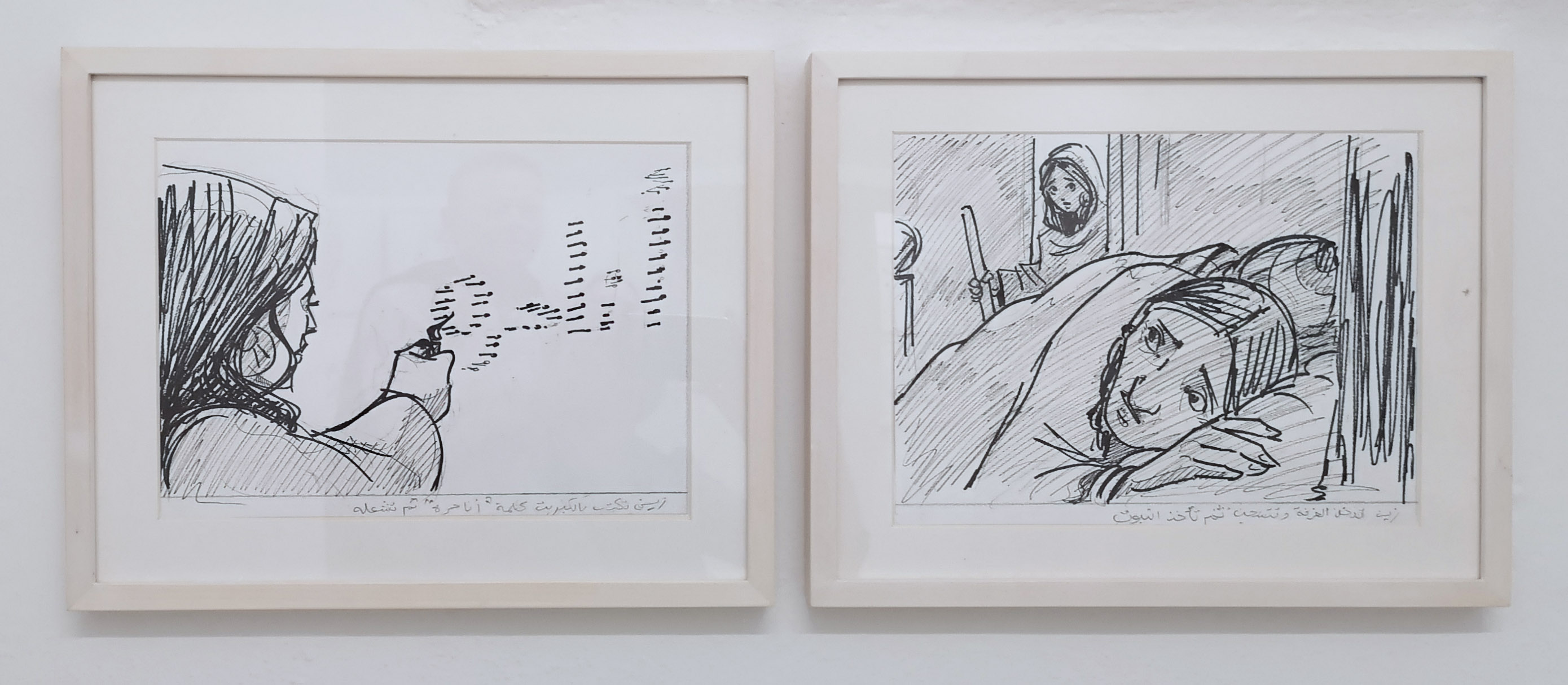

After her childhood in a village in the Egyptian countryside, the girl Zein left her home to continue her studies. In doing so, she leaves behind her family, her childhood friend and a strange, remote place: after sunset people are closed up in their houses, for fear of the mountain demon. One day, Zein travels back to her village. By now, the young woman has become a city dweller, who wants to end the fright. One night, she leaves the house. Before, she burns some matches fixed to the wall. They are arranged in form of Arabic letters. Written is “I’m free”. Taking her father’s traditional staff with her, Zein walks to the cursed mountain. Impressed by the courage, the village’s people follow her in some distance. Arrived on the peak, the young woman rams the staff into the ground and breaks down. Rushing to her, her father and her childhood friend are wondering: “Is she dead?” “Is she alive?” Herewith, the film ends and leaves us in the dark about Zein’s and the village’s further fate.

Evidently, the film recounts the story of a clash between tradition and modernity, as other artworks of the exhibition do. Moreover, Zein’s story is about her transition from a village girl into a rebellious city dweller who fights the fear-bringing practice. Has she found shelter under the wooden paddles to develop her self-conception? She struggled against the restrictive cage, braided by tradition, fear and masculine dominance and succeeded in contrast to the women at the slave market. Her act of liberation is symbolised by the burning matches. Here, fire is no longer destructive, but dynamic and emancipative. The drawing series seems to be somehow the making-of for the film, even though it is the preparatory storyboard. Its uncertain end illustrates that the struggle between tradition and modernity is not decided, but if people do not overcome the fear, they will remain trapped. Even if Moataz Nasr refers explicitly to his home region, the same battle is fought all around the world, due to globalisation. Social, scientific and economic changes are carried into the last corner. The imagination of an ancient better world still resists, is this the lost paradise?

Special thanks to Silvia Pichini from the Galleria Continua for the support.

Photos © Astrid Gallinat & Stephan Goseberg, if not mentioned otherwise