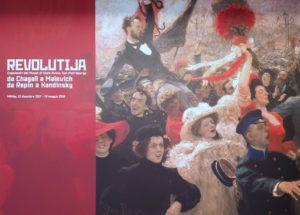

MAMbo – Museo d’Arte Moderna, Bologna

MAMbo – Museo d’Arte Moderna, Bologna

12 Decemebre 2017 – 13 May 2018

https://mostrarevolutija.it/en/

Just in time, at the end of the commemoration of 100 years of the October Revolution, the Bolognese Museum of Modern Art opens the exhibition “Revolutija: from Chagall to Malevich, from Repin to Kandinsky”. Even though, the show is initiated on occasion of the centenary of the far-reaching upheaval in Russia, it is not only aiming the events in October 1917, but also the time before and after. Since the October Revolution was not an isolated incident, the organisers are pointing back to 1905.

Starting with the Bloody Sunday in St. Petersburg in January, there were social and political riots, which lead to the October Manifesto by the Emperor Nicolas II. More or less approved by contemporaneous artistic circles, the events found expression in artworks. A significant example is the painting “17 October 1905” by Il’ja Repin, chosen as title image of the exhibition.

Though the political events, social claims and the strengthen of civil society, were not only depicted in artworks, but also changed the artistic self-conception. Already before, there was an active exchange between Russian artists and the international art scene. Some creatives had the possibility to travel to Europe, like Chagall, Repin and Kandinsky, others like Malevich saw the emerging artists in Russia, since there were numerus exhibitions showing artworks from impressionism, through fauvism and cubism.

The Russian creatives contented themselves not only with copying their international colleagues. They also went further to form diverse avant-garde movements. Correspondingly, the stylistic variations are multiple in the exhibition. Sometimes the external references are easily recognisable, like in cubo-futuristic paintings by Nathan Alt’man (Portrait of Anna Achmatova, 1915) or Natal’ja Gončarova (Cyclist, 1913). Beyond that, the self-reliant will to establish new artistic practices are evident.

The Russian creatives contented themselves not only with copying their international colleagues. They also went further to form diverse avant-garde movements. Correspondingly, the stylistic variations are multiple in the exhibition. Sometimes the external references are easily recognisable, like in cubo-futuristic paintings by Nathan Alt’man (Portrait of Anna Achmatova, 1915) or Natal’ja Gončarova (Cyclist, 1913). Beyond that, the self-reliant will to establish new artistic practices are evident.

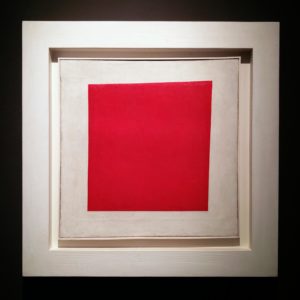

An example of interdisciplinary cooperation between visual artists, poets and composers is the futurist opera “Victory over the Sun” from 1913. Velimir Khlebnikov wrote the prologue, the libretto is contributed to Aleksei Kruchnykh and the music was composed by Mikhail Matyushin. Kazimir Malevich was responsible for the stage design. In this context, he made his first “Black Square” painting, expression of a revolution in painting. Reconstructed costumes from 2013 and a video of new production of the opera are on view, like several paintings by Malevich from 1913 to 1932. Other suprematists like Ivan Kljun, Ljubov Popova and Olga Rozanova are also represented like the constructivist Alexander Rodchenko and the pioneer of abstract painting Wassily Kandinsky.

An example of interdisciplinary cooperation between visual artists, poets and composers is the futurist opera “Victory over the Sun” from 1913. Velimir Khlebnikov wrote the prologue, the libretto is contributed to Aleksei Kruchnykh and the music was composed by Mikhail Matyushin. Kazimir Malevich was responsible for the stage design. In this context, he made his first “Black Square” painting, expression of a revolution in painting. Reconstructed costumes from 2013 and a video of new production of the opera are on view, like several paintings by Malevich from 1913 to 1932. Other suprematists like Ivan Kljun, Ljubov Popova and Olga Rozanova are also represented like the constructivist Alexander Rodchenko and the pioneer of abstract painting Wassily Kandinsky.

Besides, there are many figurative paintings, which depict the times from 1905 until the 1930s. The themes are various like the styles. Influenced by the Art Nouveau Valentin Serov portrayed Ida Rubinstein in 1910. He questioned as well the glory of the emperor’s soldiers regarding the Bloody Sunday in St. Petersburg in 1905, as an example of illustrated critique concerning the political events. However, in the 1910s, the display of farmers and washerwomen is dominant besides portraits and military with the beginning First World War. Labourers are entering in the paintings from 1917. Afterwards there are as well images of communists and their manifestations. Increasingly – due to the rise of Stalin – the influence of the new state principle of the socialist realism gets visible. This culminates in the bronze model of “The Worker and Kolkhoz Woman” by Vera Mukhina from 1936, prototype made for the monumental statue, which crowned the Russian Pavilion at the 1937 World’s Fair in Paris.

Besides, there are many figurative paintings, which depict the times from 1905 until the 1930s. The themes are various like the styles. Influenced by the Art Nouveau Valentin Serov portrayed Ida Rubinstein in 1910. He questioned as well the glory of the emperor’s soldiers regarding the Bloody Sunday in St. Petersburg in 1905, as an example of illustrated critique concerning the political events. However, in the 1910s, the display of farmers and washerwomen is dominant besides portraits and military with the beginning First World War. Labourers are entering in the paintings from 1917. Afterwards there are as well images of communists and their manifestations. Increasingly – due to the rise of Stalin – the influence of the new state principle of the socialist realism gets visible. This culminates in the bronze model of “The Worker and Kolkhoz Woman” by Vera Mukhina from 1936, prototype made for the monumental statue, which crowned the Russian Pavilion at the 1937 World’s Fair in Paris.

Initially several artists were favourable to the Bolshevik overthrow and took positions in the new Soviet Republic in artistic commissions and art schools. For a while, it seemed that in the discussion about the right style, the abstract fraction around the suprematist Malevich would prevail the figurative creations. In the following time the working conditions for figurative artists deteriorated, which lead for example Chagall to leave Russia in 1923. This might be a reason, why there is only one painting by him in the exhibition (Promenade, 1917). However, the socialist realism became doctrine in 1932. Several artists emigrated, others tried – often unsuccessfully – to a more figurative style, like Malevich, which is well illustrated by the choice of exhibited paintings. Other artists shifted to other activities and created their artworks more or less in private. Rodchenko, for example, concentrated on sports photography and organized exhibitions. Correspondingly, the two paintings by Rodchenko are both from 1918.

Initially several artists were favourable to the Bolshevik overthrow and took positions in the new Soviet Republic in artistic commissions and art schools. For a while, it seemed that in the discussion about the right style, the abstract fraction around the suprematist Malevich would prevail the figurative creations. In the following time the working conditions for figurative artists deteriorated, which lead for example Chagall to leave Russia in 1923. This might be a reason, why there is only one painting by him in the exhibition (Promenade, 1917). However, the socialist realism became doctrine in 1932. Several artists emigrated, others tried – often unsuccessfully – to a more figurative style, like Malevich, which is well illustrated by the choice of exhibited paintings. Other artists shifted to other activities and created their artworks more or less in private. Rodchenko, for example, concentrated on sports photography and organized exhibitions. Correspondingly, the two paintings by Rodchenko are both from 1918.

Overall, the exhibition presents 70 paintings and two sculptures coming from the State Russian Museum in St. Petersburg. The selected oeuvres from 1905 to 1936 summarise the partly divergent styles in Russia in the first quarter of the 19th century and the following orientation to the socialist realism. Furthermore, the curator Evgenija Petrova (Deputy Director of the State Russian Museum) and her co-curator Joseph Kiblitsky illustrate the social and political influences to art and vice versa in this period of upheaval. Maybe, the changes within the Russian society encouraged the partly revolutionary artistic inventions.