La Biennale di Venezia – 60th International Art Exhibition

La Biennale di Venezia – 60th International Art Exhibition

20 April – 24 November 2024

www.labiennale.org

The 60th edition of the International Art Exhibition was officially opened to the public on Saturday the 20th of April 2024. Until November 24, it is possible to visit the main exhibition “Foreigners Everywhere – Stranieri Ovunque” curated by Adriano Pedrosa (Brazil) with its 331 invited artists and collectives who have lived or currently live in 80 countries. Moreover, there are 87 national participations with pavilions in the Giardini, in the Arsenale and throughout the city of Venice. Besides the rich official program with 30 collateral events, there are countless exhibitions around.

Adriano Pedrosa is not only the first curator of the Biennale based in the Southern Hemisphere but also the first openly Queer curator. This is reflected in the exhibition, which concentrates on artists from the Global South, Indigenous people, and Queer creatives. Hereby, a special attention is on artists who were never represented at the Venice Biennale and a “focus is thus artists who are themselves foreigners, immigrants, expatriates, diasporic, émigrés, exiled, or refugees—particularly those who have moved between the Global South and the Global North. Migration and decolonisation are key themes here.”* as Adriano Pedrosa stated. Since the choice points to so far underrepresented groups, there are a lot of new discoveries to make, especially for euroamerican-centred art lovers.

“Foreigners Everywhere” is structured in a Nucleo Contemporaneo and a Nucleo Storico with three sections: Abstractions, Portraits (both in the Central Pavilion, Giardini) and Italians Everywhere (in the Arsenale). Since the Nucleo Storico focusses on artworks from the years 1915 to 1990, there is a large domination of paintings but also works on paper and sculpture. This is a certain challenge for the multi-media spoiled visitor. Instead of moving and sounding videos and installations, one has to deal with still pictures, which are speaking another language than the familiar visual world of the present. Moreover, the subjects and the visual vocabulary of the Global South differs from occidental approaches. Euroamericans might feel uneasy, like a stranger. However, if one takes the plunge, it is a revealing experience, even though it is sometimes necessary to read the given explanations to the artists and artworks. In the following, we will describe our visit in the Central Pavilion in the Giardini.

“Foreigners Everywhere” is structured in a Nucleo Contemporaneo and a Nucleo Storico with three sections: Abstractions, Portraits (both in the Central Pavilion, Giardini) and Italians Everywhere (in the Arsenale). Since the Nucleo Storico focusses on artworks from the years 1915 to 1990, there is a large domination of paintings but also works on paper and sculpture. This is a certain challenge for the multi-media spoiled visitor. Instead of moving and sounding videos and installations, one has to deal with still pictures, which are speaking another language than the familiar visual world of the present. Moreover, the subjects and the visual vocabulary of the Global South differs from occidental approaches. Euroamericans might feel uneasy, like a stranger. However, if one takes the plunge, it is a revealing experience, even though it is sometimes necessary to read the given explanations to the artists and artworks. In the following, we will describe our visit in the Central Pavilion in the Giardini.

The Historic Nuclei surrounded by Contemporary Creations

After a prelude by the title-giving neon by the artist collective Claire Fontaine and the installations “Topak Ev” and “Exile is a hard job” by this years’ Golden-Lion-for-Lifetime-Achievement-holder Nil Yalter, visitors immerse into Abstractions, the first part of the Nucleo Storico. It features 37 artists who worked in Africa, Asia, the Middle East and Latin America in the second half of the 20th century. Here, a special attention is on the Casablanca School of painters, which emerged in the post-independence Morocco of the 1960s. Besides European canonical abstract geometric, or constructivist references, regional influences become evident. Instead of primary colours and rigid orthogonal grids, there are secondary and even tertiary shades and undulating lines (Mohammad Ehsaei: Untitled, 1974, oil on canvas and Fahrelnissa Zeid: Untitled 1955, oil on canvas), margins are blurred, and forms are overlapping (Nena Saguil: Untitled (Abstract), 1972, oil on canvas). The painting support is not only canvas, but also could be wool threads and textiles or bamboos (Eduardo Terrazas: 1.1.91, 1970-72, wool threads on wooden board covered with Campeche wax).

After a prelude by the title-giving neon by the artist collective Claire Fontaine and the installations “Topak Ev” and “Exile is a hard job” by this years’ Golden-Lion-for-Lifetime-Achievement-holder Nil Yalter, visitors immerse into Abstractions, the first part of the Nucleo Storico. It features 37 artists who worked in Africa, Asia, the Middle East and Latin America in the second half of the 20th century. Here, a special attention is on the Casablanca School of painters, which emerged in the post-independence Morocco of the 1960s. Besides European canonical abstract geometric, or constructivist references, regional influences become evident. Instead of primary colours and rigid orthogonal grids, there are secondary and even tertiary shades and undulating lines (Mohammad Ehsaei: Untitled, 1974, oil on canvas and Fahrelnissa Zeid: Untitled 1955, oil on canvas), margins are blurred, and forms are overlapping (Nena Saguil: Untitled (Abstract), 1972, oil on canvas). The painting support is not only canvas, but also could be wool threads and textiles or bamboos (Eduardo Terrazas: 1.1.91, 1970-72, wool threads on wooden board covered with Campeche wax).

These two sections of the Nucleo Storico are surrounded by artworks of the first part of the Nucleo Contemporaneo. One hall is dedicated to Pablo Delano’s installation “The Museum of the Old Colony” from 2024. Photos, documents, and furniture ensembles, accompanied by product placements of American merchandise articles like drinks and a Barbie, illustrate Puerto Rico’s colonialisation by the United States. Still today the Caribbean state is an unincorporated territory of the United States, in consequence the habitants are US-Citizens. Even though represented by the US in foreign policy, tax paying and economic dependence of the US, the Puerto Ricans have no right to vote for national elections. They are strangers in their own country.

These two sections of the Nucleo Storico are surrounded by artworks of the first part of the Nucleo Contemporaneo. One hall is dedicated to Pablo Delano’s installation “The Museum of the Old Colony” from 2024. Photos, documents, and furniture ensembles, accompanied by product placements of American merchandise articles like drinks and a Barbie, illustrate Puerto Rico’s colonialisation by the United States. Still today the Caribbean state is an unincorporated territory of the United States, in consequence the habitants are US-Citizens. Even though represented by the US in foreign policy, tax paying and economic dependence of the US, the Puerto Ricans have no right to vote for national elections. They are strangers in their own country.

Another aspect of colonialisation illustrates the video installation “Gaddafi in Rome: Anatomy of a Friendship” by Alessandra Ferrini from 2024. The work refers to the treaty of friendship, partnership and cooperation between Italy and Libya in 2008 and ratified one year later, in occasion of Muammar Gaddafi’s visit in Rome, featured in a video. After the painful colonisation, the at the time Libyan leader and the Italian prime minister Silvio Berlusconi agreed reparation payments in an amount of 5 billion dollars, payable within 20 years, a widespread cooperation and the combat against illegal migration from Libya to Italy. With the treaty Italy recognised its responsibility for the colonial injustices, which enabled a closing of the past. It was the first time in history that a country had apologized and compensated for its previous colonisation. Nevertheless, the treaty was criticised regarding the human rights of refugees and was at the same time a fundament for later treaties to push back migrants in the Mediterranean. Moreover, Italy profited economically from the new partnership by installing Italian enterprises in the former colony, especially in the energy sector.

Another aspect of colonialisation illustrates the video installation “Gaddafi in Rome: Anatomy of a Friendship” by Alessandra Ferrini from 2024. The work refers to the treaty of friendship, partnership and cooperation between Italy and Libya in 2008 and ratified one year later, in occasion of Muammar Gaddafi’s visit in Rome, featured in a video. After the painful colonisation, the at the time Libyan leader and the Italian prime minister Silvio Berlusconi agreed reparation payments in an amount of 5 billion dollars, payable within 20 years, a widespread cooperation and the combat against illegal migration from Libya to Italy. With the treaty Italy recognised its responsibility for the colonial injustices, which enabled a closing of the past. It was the first time in history that a country had apologized and compensated for its previous colonisation. Nevertheless, the treaty was criticised regarding the human rights of refugees and was at the same time a fundament for later treaties to push back migrants in the Mediterranean. Moreover, Italy profited economically from the new partnership by installing Italian enterprises in the former colony, especially in the energy sector.

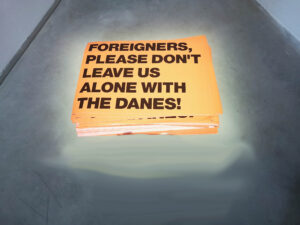

Besides economic benefits for Italy, the Italian-Libyan treaty established the basis for the still enduring rejection of refugees of the European Union by bilateral agreements. Also the Danish artist collective Superflex worries about the increasing hostility towards strangers in their country. Already in 2002, when Denmark had the presidency of the EU, they printed posters with the plea: “Foreigners, please don’t leave us alone with the Danes!” and distributed them in the streets of Copenhagen. This ironic comment was reprinted during the years and became a statement and cultural object, presented in restaurants and bars to demonstrate the opposition against xenophobia. Not only the migrants feel strangers, but also people who refuse to accept anti-immigrant and national ideology. In the Central Pavilion, a stack of posters and photos of their installation in various spaces, is presented in a light box, illustrates this process. This presentation with its allusion to advertising underlines the appropriation of the project.

Besides economic benefits for Italy, the Italian-Libyan treaty established the basis for the still enduring rejection of refugees of the European Union by bilateral agreements. Also the Danish artist collective Superflex worries about the increasing hostility towards strangers in their country. Already in 2002, when Denmark had the presidency of the EU, they printed posters with the plea: “Foreigners, please don’t leave us alone with the Danes!” and distributed them in the streets of Copenhagen. This ironic comment was reprinted during the years and became a statement and cultural object, presented in restaurants and bars to demonstrate the opposition against xenophobia. Not only the migrants feel strangers, but also people who refuse to accept anti-immigrant and national ideology. In the Central Pavilion, a stack of posters and photos of their installation in various spaces, is presented in a light box, illustrates this process. This presentation with its allusion to advertising underlines the appropriation of the project.

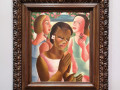

Malangatana Valente Ngwenya’s “To the Clandestine Maternity Home” from 1961 (oil on canvas) is a painting from the early, strongly political influenced period of the Mozambican artist. Its issue is the lack of self-determination of Mozambique’s women under the Portuguese colonial rule and the associated control over the female body. As response to this alienation, arose clandestine maternity homes and abortion networks. In the painting, this background is hardly to recognise, but it is strongly populated. The human figures are superposed and overlapped. Although the ethnicities are not always identifiable the genre is mostly apparent. Evident is, that there are many pregnant women with significant open eyes and striking, mostly closed mouths. This could be interpreted that the women have no right to speak, despite a present awareness. They are foreigners in their society without rights for them. Noteworthy is the attention a male artist paid to female problems, especially in the early 1960s.

Malangatana Valente Ngwenya’s “To the Clandestine Maternity Home” from 1961 (oil on canvas) is a painting from the early, strongly political influenced period of the Mozambican artist. Its issue is the lack of self-determination of Mozambique’s women under the Portuguese colonial rule and the associated control over the female body. As response to this alienation, arose clandestine maternity homes and abortion networks. In the painting, this background is hardly to recognise, but it is strongly populated. The human figures are superposed and overlapped. Although the ethnicities are not always identifiable the genre is mostly apparent. Evident is, that there are many pregnant women with significant open eyes and striking, mostly closed mouths. This could be interpreted that the women have no right to speak, despite a present awareness. They are foreigners in their society without rights for them. Noteworthy is the attention a male artist paid to female problems, especially in the early 1960s.

Interactions between the Western Hemisphere and the Global South

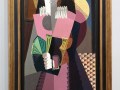

Bertina Lopes was also born in Mozambique but educated in Portugal. She left her home country in 1961, first for Portugal and then Italy. In her work the knowledge of Modernism and especially Cubism is manifest, like in “Griddo grand” (Big Cry) from 1970 (oil on canvas). The allusion to Picasso’s Guernica is obvious, despite the much smaller format (150 cm x 150 cm) and much less protagonists. Considering the occasion, it was the Operation Gordian Knot, a campaign of the Portuguese military against the Mozambican guerrillas, this resemblance does not seem incidental. However, the painting also reveals Bertina Lopes’ personal style, for example by the paintbrush and the introduction of a Mozambican mask. An interpenetration of occidental and African elements is the result from both influences.

Bertina Lopes was also born in Mozambique but educated in Portugal. She left her home country in 1961, first for Portugal and then Italy. In her work the knowledge of Modernism and especially Cubism is manifest, like in “Griddo grand” (Big Cry) from 1970 (oil on canvas). The allusion to Picasso’s Guernica is obvious, despite the much smaller format (150 cm x 150 cm) and much less protagonists. Considering the occasion, it was the Operation Gordian Knot, a campaign of the Portuguese military against the Mozambican guerrillas, this resemblance does not seem incidental. However, the painting also reveals Bertina Lopes’ personal style, for example by the paintbrush and the introduction of a Mozambican mask. An interpenetration of occidental and African elements is the result from both influences.

An infiltration of various influences is also reflected in Wifredo Lam’s “Untitled (Mujer Caballo)” realised between 1942 and 1946 (oil on canvas) during the artists temporary return to Cuba, his home island. Besides impacts of surrealism and cubism, the subject comes from Santeria, a hybrid figure of woman and horse. At the same time, the horse-headed woman represents anticolonial spiritual force.

An infiltration of various influences is also reflected in Wifredo Lam’s “Untitled (Mujer Caballo)” realised between 1942 and 1946 (oil on canvas) during the artists temporary return to Cuba, his home island. Besides impacts of surrealism and cubism, the subject comes from Santeria, a hybrid figure of woman and horse. At the same time, the horse-headed woman represents anticolonial spiritual force.

The Curruchich Family

Relatively free from external influence are the paintings by Andrés Curruchich (1891-1969). He was one of the most international recognised painters from the Kaqchikel people in San Juan Comalapa, Guatemala. Therefore, his work had an impact on other Guatemalan artists. In his naïve style he depicted for example the procession for the patron of his hometown, Saint John, in 1966 (oil on canvas, 17,13 inch x 19 inch (43,51 cm x 48,26 cm)). Awestruck indigenes are carrying colourful alters.

Relatively free from external influence are the paintings by Andrés Curruchich (1891-1969). He was one of the most international recognised painters from the Kaqchikel people in San Juan Comalapa, Guatemala. Therefore, his work had an impact on other Guatemalan artists. In his naïve style he depicted for example the procession for the patron of his hometown, Saint John, in 1966 (oil on canvas, 17,13 inch x 19 inch (43,51 cm x 48,26 cm)). Awestruck indigenes are carrying colourful alters.

The works of his two granddaughters Paula Nicho Cumez and Rosa Elena Curruchich are supposed to be close to him in the exhibition. Unfortunately, the paintings by Paula Nicho Cumez had not arrived in the first days of the Biennale and will be on view later, whereas Rosa Elena Curruchich (1958-2005) miniatures were already on display.

The works of his two granddaughters Paula Nicho Cumez and Rosa Elena Curruchich are supposed to be close to him in the exhibition. Unfortunately, the paintings by Paula Nicho Cumez had not arrived in the first days of the Biennale and will be on view later, whereas Rosa Elena Curruchich (1958-2005) miniatures were already on display.

Even though there are stylistic references to her grandfather, there are ample distinctions. First of all, Rosa Elena Curruchich identified herself as Maya Kaqchikel artist. Her subjects are the daily life, work and festivities of women in her Indigenous community. This female focus is not surprising, since her family including her grandfather and her husband, tried to prevent her artistic activities. She had to work in secrecy, thus her small formats. Additionally, the size allowed her to transport her paintings to Guatemala City and sell them, even during the civil war (1960-1996). Instead of being addressed to tourists, Rosa Elena Curruchich, they are directed to the Guatemalan society to point to her transformations, in particular to the progressive development of gender equality. On her way to recognition, she often must has felt abandoned, especially by her own family.

Even though there are stylistic references to her grandfather, there are ample distinctions. First of all, Rosa Elena Curruchich identified herself as Maya Kaqchikel artist. Her subjects are the daily life, work and festivities of women in her Indigenous community. This female focus is not surprising, since her family including her grandfather and her husband, tried to prevent her artistic activities. She had to work in secrecy, thus her small formats. Additionally, the size allowed her to transport her paintings to Guatemala City and sell them, even during the civil war (1960-1996). Instead of being addressed to tourists, Rosa Elena Curruchich, they are directed to the Guatemalan society to point to her transformations, in particular to the progressive development of gender equality. On her way to recognition, she often must has felt abandoned, especially by her own family.

Loneliness within the Crowd

Another form of loneliness shows Dean Sameshima’s photo series “being alone” from 2022. At first glance, one sees single persons sitting in front of a white screen in a cinema. Since the Berlin based US-artist emptied the screen from the film images, the bystander needs to know about the artist’s motivation and approach. In this part of the long-term series, he documented porn cinemas in Berlin and refers with that to clandestine sexual practices in particular in the Queer community.

Another form of loneliness shows Dean Sameshima’s photo series “being alone” from 2022. At first glance, one sees single persons sitting in front of a white screen in a cinema. Since the Berlin based US-artist emptied the screen from the film images, the bystander needs to know about the artist’s motivation and approach. In this part of the long-term series, he documented porn cinemas in Berlin and refers with that to clandestine sexual practices in particular in the Queer community.

Louis Fratino also deals with the otherness of LGBTQ+ people. His paintings remind expressionism and New Objectivity (in German: Neue Sachlichkeit). “Kissing my Foot” (2024, oil on canvas) shows in the central position a bare man who is kissing a foot. He is surrounded by other legs that are difficult to relate to a body. The author, whose foot is kissed rests invisible besides his extremity. Despite the affectionate gesture and the entangledness of the legs the bodies seem to be isolated from each other. “An Argument” (2021, oil on canvas) points to another separation between individuals. The observer glances through a window into a room, where a naked man is sleeping on a sofa. His presumed partner lies in front of the frame, also unclothed. The title suggests a quarrel which leaves both alone. Prisoned by the, from the society, imposed otherness, the protagonists feel alone, whether it be in private or intimate company.

After an odyssey from foster parents, children’s home and domestic servant and caregiver in Canada, the English Madge Gill (1882–1961) encountered spiritualism at the home of her aunt. Due to acall experience with ghost apparition at the age of 38, she started to draw and created thousands of works in the following 40 years. Feeling as a medium, she sketched on various sizes, from postcard-format to huge sheets of fabric, like the “Crucifixion of the Soul” from 1936 which is 147 cm x 1062 cm. Here, corresponding to her recurrent motifs there are women with delicate faces and striking eyes. They are embedded in geometric chequered patters and organic ornamentation. It is a mysterious, strange world, where the individuals seem to be isolated. Maybe they are self-portraits, portraits of her deceased daughter, or of her spirit guide. They seem to express a suffering to a world, were the artist felt left alone.

After an odyssey from foster parents, children’s home and domestic servant and caregiver in Canada, the English Madge Gill (1882–1961) encountered spiritualism at the home of her aunt. Due to acall experience with ghost apparition at the age of 38, she started to draw and created thousands of works in the following 40 years. Feeling as a medium, she sketched on various sizes, from postcard-format to huge sheets of fabric, like the “Crucifixion of the Soul” from 1936 which is 147 cm x 1062 cm. Here, corresponding to her recurrent motifs there are women with delicate faces and striking eyes. They are embedded in geometric chequered patters and organic ornamentation. It is a mysterious, strange world, where the individuals seem to be isolated. Maybe they are self-portraits, portraits of her deceased daughter, or of her spirit guide. They seem to express a suffering to a world, were the artist felt left alone.Giulia Andreani’s nearly photo-realistic paintings are held primarily in Payne’s Grey. This reminds old photographs and so is the source of inspiration. She reproduces, alters and combines motifs from personal or archival images. The in the Nucleo Contemporaneo presented pictures are in dialogue with Madge Gill. First of all, because arranged in the same room, but also because Giulia Andreani tried to connect Madge Gill’s history and the history of women’s access to artistic practice at the turn to the 20th century. At the same time, she researches for a link between feminism and spiritualism. There is a fashionable woman melting on the stairs “Pretty Vacant (Diva Derelitta)” (2024), in the group portrait of cutting and sewing school (La scuola di taglio e cucito” (2023)), only the central women are elaborated, the surrounding pupils seem to fade in fog and the “Conservative Ghost (Aetas Ferrea) (2024)”, features a woman with speech bubble. In it is a woman with her crying child depicted. Are these signs of influence from an interworld? Conversely, two other pictures show the working conditions of girls in a kind of laboratory (Le Fanciulle Laboriose (2024)) and the women’s practical approaches to painting. These pioneers at the turn of the century were foreigners in a masculine dominated world.

Strategies to overcome Repression With the multi-cycle video & sound installation “Personal Accounts” (2024) by Gabrielle Goliath we are coming back into the contemporary world. Since 2014, the South African artist interviews black, brown, indigenous, femme, queer, non-binary, and trans individuals, while talking about their everyday experience with patriarchal, racializing, and colonial violence and oppression and strategies to withstand it. However, in the presented videos, the spoken words are resected, so that the observer can only perceive the paralinguistic expressions like gesture, breaths, swallows, sighs, cries, humming and even laughter. Herewith, arise a universal language, which supports understanding and compassion beyond downplaying verbal critics. It could be an approach of empowerment for rejected groups against entrenched repressive structures.

With the multi-cycle video & sound installation “Personal Accounts” (2024) by Gabrielle Goliath we are coming back into the contemporary world. Since 2014, the South African artist interviews black, brown, indigenous, femme, queer, non-binary, and trans individuals, while talking about their everyday experience with patriarchal, racializing, and colonial violence and oppression and strategies to withstand it. However, in the presented videos, the spoken words are resected, so that the observer can only perceive the paralinguistic expressions like gesture, breaths, swallows, sighs, cries, humming and even laughter. Herewith, arise a universal language, which supports understanding and compassion beyond downplaying verbal critics. It could be an approach of empowerment for rejected groups against entrenched repressive structures.

“Foreigners Everywhere – Stranieri Ovunque” features artists from marginalised regions, ethnic groups and genders. To focus on them is for the curator Adriano Pedrosa a necessary settle of a historic debt.* Herewith he is not alone, as for example the 15th documenta in Kassel showed. Nevertheless, one might question if, in the current situation of existential threat by multiple conflicts and the climate-crisis, art shouldn’t react to those present conditions. Though discovering the not so well-known or the unknown might help to a better understanding of other cultures and arouse interest to learn more about the others. This could be a first step for more sensibility which might, in the long term, help to avoid conflicts.

* Adriano Pedrosa in his statement for the Venice Biennale, https://www.labiennale.org/en/press, press-kit, 22/04/2024

Text: Astrid Gallinat

Photos © Astrid Gallinat & Stephan Goseberg, if not mentioned otherwise