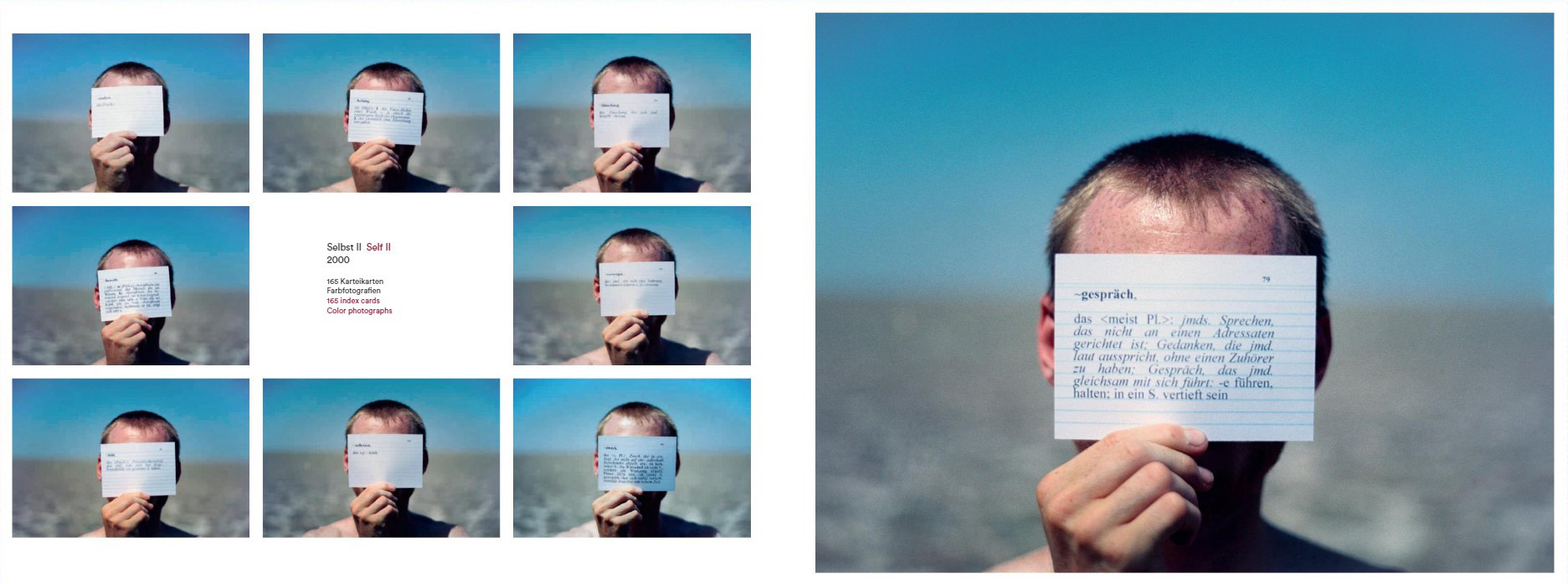

Thomas Neumann’s exhibition “Exact Confidence Limits. Photography since 1994” at the Weltkunstzimmer in Düsseldorf recently closed. For those, who missed the show, there are eight video tours through the exhibition online (in German). Additionally, Hatje Cantz Publishers released a deepening book with the same name on the exhibition. It displays most of the works and is complemented with a poem by Durs Grünbein and texts by Karl Schlögel, Eva Pluhařová-Grigienė (based on an interview with the artist by Gabriele Muschter and Uwe Warnke) (German/English). For “Exact Confidence Limits” Thomas looked back to his oeuvre since 1994, when he travelled for the first time to Moscow. Later he undertook many voyages to the countries of the former Soviet Union. Moreover, he researched archives and stepped back into the visual history of these states, but also into his own artistic and personal past. We questioned Thomas about his motivations, methods and background.

Thomas Neumann’s exhibition “Exact Confidence Limits. Photography since 1994” at the Weltkunstzimmer in Düsseldorf recently closed. For those, who missed the show, there are eight video tours through the exhibition online (in German). Additionally, Hatje Cantz Publishers released a deepening book with the same name on the exhibition. It displays most of the works and is complemented with a poem by Durs Grünbein and texts by Karl Schlögel, Eva Pluhařová-Grigienė (based on an interview with the artist by Gabriele Muschter and Uwe Warnke) (German/English). For “Exact Confidence Limits” Thomas looked back to his oeuvre since 1994, when he travelled for the first time to Moscow. Later he undertook many voyages to the countries of the former Soviet Union. Moreover, he researched archives and stepped back into the visual history of these states, but also into his own artistic and personal past. We questioned Thomas about his motivations, methods and background.

Astrid Gallinat: The exhibition/book „Exact Confidence Limits“ shows a selection of your works since 1994. Many are originating from your visits of the states of the former Soviet Union. How are you connected to these countries?

Thomas Neumann: As I was born 1975 in Eastern Germany, I have found myself from the very young age influenced by the cosmos of Communism. In school, we were taught about the myths of the Soviet Civilization. Especially books about space technology and future cities had an impact on me. Later the Soviet Empire did collapse and I was wondering if all the myths were fairytales or kind of fata morgana. In the very early 90s, our high school had an exchange with pupils from Minsk, Belarus. So we went there and could see the reality of the post-soviet era. It has triggered me to see more and to learn more Russian language. Afterwards a friend and I travelled during the summer holidays through the Baltic countries (Lithuania, Latvia, Estonia). And in 1994 I have stayed in Moscow for a month to enrol in a language school. After that month, my friend and I took the train to Sochi and we have spent some days in the Caucasus Mountains.

Thomas Neumann: As I was born 1975 in Eastern Germany, I have found myself from the very young age influenced by the cosmos of Communism. In school, we were taught about the myths of the Soviet Civilization. Especially books about space technology and future cities had an impact on me. Later the Soviet Empire did collapse and I was wondering if all the myths were fairytales or kind of fata morgana. In the very early 90s, our high school had an exchange with pupils from Minsk, Belarus. So we went there and could see the reality of the post-soviet era. It has triggered me to see more and to learn more Russian language. Afterwards a friend and I travelled during the summer holidays through the Baltic countries (Lithuania, Latvia, Estonia). And in 1994 I have stayed in Moscow for a month to enrol in a language school. After that month, my friend and I took the train to Sochi and we have spent some days in the Caucasus Mountains.

A.G.: During your first visits, the spirit in these countries was about a radical change due to the collapse of the Soviet system. How did this atmosphere enter into your photos?

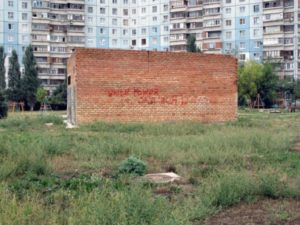

T.N.: In Eastern Germany we also had the experience of a system change, but in the former Soviet the scale of the change was much bigger and more radical. As a lucky East-German whose country was reunited with the wealthy west, it was painful to see the situation in Russia. Mostly the intelligentsia did suffer a lot, because they were not used to make business. I as a photographer did avoid taking pictures of poverty and destruction. I have felt respect and sympathy towards these people, who have tried to figure out a new identity personally and nationally. In the beginning there are some persons in my photographs, later they have disappeared. In terms of architecture it was difficult, because all the Soviet cityscapes were wrapped in new advertising. Besides these travel photos, I have made – back in Germany – some works related to code systems like secret languages and symbols, which you can read but not understand. If I look back, these works seem to be a metaphor for photography: You can see something but don’t necessarily understand anything.

T.N.: In Eastern Germany we also had the experience of a system change, but in the former Soviet the scale of the change was much bigger and more radical. As a lucky East-German whose country was reunited with the wealthy west, it was painful to see the situation in Russia. Mostly the intelligentsia did suffer a lot, because they were not used to make business. I as a photographer did avoid taking pictures of poverty and destruction. I have felt respect and sympathy towards these people, who have tried to figure out a new identity personally and nationally. In the beginning there are some persons in my photographs, later they have disappeared. In terms of architecture it was difficult, because all the Soviet cityscapes were wrapped in new advertising. Besides these travel photos, I have made – back in Germany – some works related to code systems like secret languages and symbols, which you can read but not understand. If I look back, these works seem to be a metaphor for photography: You can see something but don’t necessarily understand anything.

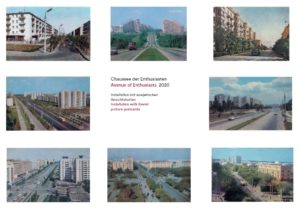

A.G.: Later, you undertook a nearly archaeological research for traces of the bygone system. There are photos and postcards of Soviet architecture. What is your interest in these buildings?

T.N.: In the 90s, the former Soviet countries did develop rapidly. All the countries tried to dig out their own national identities. The Baltic countries, Ukraine, the central Asian countries. So they also did change the public space according to their new future and new (non-Soviet) past. In my case, I have felt that I was artistically more interested in the heritage of the Soviet and less in the transformation processes. But for my interest in the Soviet I was 10 years too late and I have found myself in a position of an archaeologist. Under the layer of the contemporary, I was looking for the Soviet remnant. And so I have found photobooks and picture postcards as media of great interest. In these publications, you can see the official view on Soviet cities, landscapes and people. That official view is ambivalent because you can see the reality and at the same moment, you can read the rules of censorship and the „corrected reality“. And in a broader sense these mechanisms are inherent in photography generally.

T.N.: In the 90s, the former Soviet countries did develop rapidly. All the countries tried to dig out their own national identities. The Baltic countries, Ukraine, the central Asian countries. So they also did change the public space according to their new future and new (non-Soviet) past. In my case, I have felt that I was artistically more interested in the heritage of the Soviet and less in the transformation processes. But for my interest in the Soviet I was 10 years too late and I have found myself in a position of an archaeologist. Under the layer of the contemporary, I was looking for the Soviet remnant. And so I have found photobooks and picture postcards as media of great interest. In these publications, you can see the official view on Soviet cities, landscapes and people. That official view is ambivalent because you can see the reality and at the same moment, you can read the rules of censorship and the „corrected reality“. And in a broader sense these mechanisms are inherent in photography generally.

A.G.: Stylistically the series “Pictures from Utopia” is striking. Here you edited historic photos from Eisenhüttenstadt. How does this town of the former GDR get into the context of „Exact Confidence Limits“?

T.N.: Eisenhüttenstadt (120 km eastward from Berlin) was built as Stalinstadt in 1952 and was called the „First socialist town in Germany“. It was inspired by Soviet town planning and after the disaster of the 2nd WW a promising project – a new comfortable town for the working-class in order to form the „New socialist human“. At the end of 1950ies and later on there were some photobooks published about that town. The photos show the best views of Stalinstadt and their inhabitants. As the greenery was still small the architecture was perfectly depicted. Especially kids were shown very often as the fortune generation of the future. As I know about the mechanism of photography I was interested to find out more about these photographs. So I have tried to dive into these photographs to find invisible aspects in there. You can understand it as a new interpretation of the original pictorial content. For me it was the first digital work and it gave me more tools for creating images. Especially in terms of colouring, it opened up new possibilities.

T.N.: Eisenhüttenstadt (120 km eastward from Berlin) was built as Stalinstadt in 1952 and was called the „First socialist town in Germany“. It was inspired by Soviet town planning and after the disaster of the 2nd WW a promising project – a new comfortable town for the working-class in order to form the „New socialist human“. At the end of 1950ies and later on there were some photobooks published about that town. The photos show the best views of Stalinstadt and their inhabitants. As the greenery was still small the architecture was perfectly depicted. Especially kids were shown very often as the fortune generation of the future. As I know about the mechanism of photography I was interested to find out more about these photographs. So I have tried to dive into these photographs to find invisible aspects in there. You can understand it as a new interpretation of the original pictorial content. For me it was the first digital work and it gave me more tools for creating images. Especially in terms of colouring, it opened up new possibilities.

A.G.: Moreover, you made landscape photography, which does not intend to depict the beauty of the scenery, but refers to history. What is your approach in these works?

T.N.: In terms of photography, I am always asking myself: Is history visible? Or what is the visibility of history? After my first visit to Yakutia (remote area in Russia) in winter 2012, I was fascinated by the white and vast landscape over there. There is the so-called „Road of the bones“, which connects Magadan and Yakutsk in a 2000 km distance. It was part of the infrastructure built by forced labour of the Gulag camps during the Stalin era. For gold and silver and also uranium mining 100 thousands of soviet people were forced to work there and a lot of them did not survive the harsh climate and labour. So I have travelled to that region three times in winter to take photographs of „historical landscapes“. The white snow is covering everything, even the history. Nothing is visible and white is hard to photograph. With that idea in mind I have tried to find places and views, where the „historical landscapes“ can start to tell their stories.

T.N.: In terms of photography, I am always asking myself: Is history visible? Or what is the visibility of history? After my first visit to Yakutia (remote area in Russia) in winter 2012, I was fascinated by the white and vast landscape over there. There is the so-called „Road of the bones“, which connects Magadan and Yakutsk in a 2000 km distance. It was part of the infrastructure built by forced labour of the Gulag camps during the Stalin era. For gold and silver and also uranium mining 100 thousands of soviet people were forced to work there and a lot of them did not survive the harsh climate and labour. So I have travelled to that region three times in winter to take photographs of „historical landscapes“. The white snow is covering everything, even the history. Nothing is visible and white is hard to photograph. With that idea in mind I have tried to find places and views, where the „historical landscapes“ can start to tell their stories.

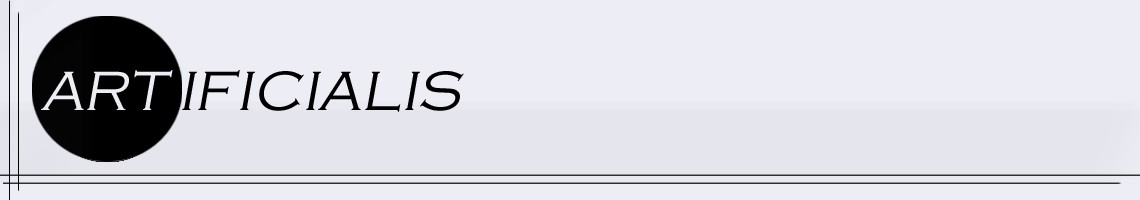

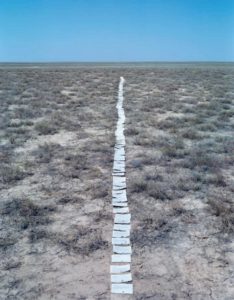

A.G.: In the series “Self” you worked with index cards. For “Self I” you placed the cards in a landscape. Here the rather “documentary” approach and the self-reflexion are mixed. How does your personal background correlate to the Soviet past?

T.N.: For that project I have printed all German words starting with „self“ with their explanation from a dictionary/lexicon on index cards. There are 165 words ranging from „Selbstanalyse“ (self-analysis) to „Selbstzweifel“ (self-doubts). I was fascinated from the idea, that a language as a manmade system tries to find a definition of „Self“. And on the other hand it seemed to me a good metaphor for the egocentric way of thinking. At the same time (around 2000 and 2001) I felt in love with the emptiness of the Kazakhstan steppe landscape. There you have the ground and the sky and in-between the horizon as illusionary line. With the index cards I did several installations and finally I took them with me to Kazakhstan and placed them into that landscape. It is a very abstract landscape, which I did understand as a stage, where people do act on it.

T.N.: For that project I have printed all German words starting with „self“ with their explanation from a dictionary/lexicon on index cards. There are 165 words ranging from „Selbstanalyse“ (self-analysis) to „Selbstzweifel“ (self-doubts). I was fascinated from the idea, that a language as a manmade system tries to find a definition of „Self“. And on the other hand it seemed to me a good metaphor for the egocentric way of thinking. At the same time (around 2000 and 2001) I felt in love with the emptiness of the Kazakhstan steppe landscape. There you have the ground and the sky and in-between the horizon as illusionary line. With the index cards I did several installations and finally I took them with me to Kazakhstan and placed them into that landscape. It is a very abstract landscape, which I did understand as a stage, where people do act on it.

Only in 2019 when I started to arrange the exhibition “Exact Confidence Limits” I was aware that the work is a link between my search of identity and the Soviet background.

A.G.: In “Self II” you enter into the image space yourself. In the earlier title-giving triptych “Exact Confidence Limits” you are also depicted, but in another form. What is the background of “Exact Confidence Limits”?

A.G.: In “Self II” you enter into the image space yourself. In the earlier title-giving triptych “Exact Confidence Limits” you are also depicted, but in another form. What is the background of “Exact Confidence Limits”?

T.N.: Photographers usually do prefer to hide behind a camera instead being exposed. In these two works I am visually part of the work, but at the same moment hidden. In „Self II“ I do hide myself behind the index cards of the German words starting with „Self-“. So it is the game with photography that there is always something hidden behind the surface. And in the triptych “Exact Confidence Limits” the mathematic formula is projected at my body and the shadow of a camera blackens me off partially. In the 90ies, I was interested in abstract sign systems. In forms of signs and figures, human beings have always tried to explain the world. And mathematics is the most abstract form of it. With “Exact Confidence Limits” you can calculate the probability and randomness of an occurrence. First of all I like the term “Exact Confidence Limits” as poetry and secondly the idea to calculate even the randomness of something is a metaphor for the will to master even the uncontrollable.

A.G.: Besides these two self-portraying series, there are not many works, which are showing people. If so, they are mostly displayed from the far. An exception is “homo sovieticus” where you opposed colour photographs of monuments to newspaper images from the Pravda. Why is here the depicting of people important to you here? About what does the series talk?

T.N.: That is true, people are not in focus of my works. In the early works of 1994/95 you can find some, but later only as a small element. In „homo sovieticus“ you can see Soviet newspaper images with people, but not portraits I did. On these newspaper photographs you can see the „homo sovieticus“ in two ways. First is the propaganda layer of these photographed persons, second you can imagine the „real“ person of that photograph, who has struggled in the Soviet reality, whose parents or relatives disappeared in 2nd WW or the Stalin’s Gulag labour camps. I personally have my doubts about doing portrait photographs. Whom should I photograph and what are these photos talking about. Probably it is my personal „Confidence limit“, which does not allow me doing portraits.

T.N.: That is true, people are not in focus of my works. In the early works of 1994/95 you can find some, but later only as a small element. In „homo sovieticus“ you can see Soviet newspaper images with people, but not portraits I did. On these newspaper photographs you can see the „homo sovieticus“ in two ways. First is the propaganda layer of these photographed persons, second you can imagine the „real“ person of that photograph, who has struggled in the Soviet reality, whose parents or relatives disappeared in 2nd WW or the Stalin’s Gulag labour camps. I personally have my doubts about doing portrait photographs. Whom should I photograph and what are these photos talking about. Probably it is my personal „Confidence limit“, which does not allow me doing portraits.

A.G.: Another exception is the photo “100 Years Great October Socialist Revolution”, which in the book stands representative for a video of the exhibition. What is the content of the video?

T.N.: In the video “ ” you see a group of people. They form a group photograph, which is a traditional genre in photography. It is not about the individual, but about a group identity. And it is frozen into a photograph, into a representation. That group photograph was the end of the “100 Years Great October Socialist Revolution” meeting in Magadan, a town known as the headquarter of the Far East Gulag labour camp system. There was a small parade and some speeches beside the Lenin statue. When the photographer called up for a group photo, I just hurried up to stand beside her to catch the moment as well. Intuitively I have also started recording with a video camera and have just recorded around an hour after the group photo. So the group turned into individuals, some go home, some talk to each other, some start to clean up. And the more people leave the square the more pigeons come back and re-enter the square. A child finds a leftover red balloon and starts to play with it and a dog is chasing the pigeons. Live goes on.

” you see a group of people. They form a group photograph, which is a traditional genre in photography. It is not about the individual, but about a group identity. And it is frozen into a photograph, into a representation. That group photograph was the end of the “100 Years Great October Socialist Revolution” meeting in Magadan, a town known as the headquarter of the Far East Gulag labour camp system. There was a small parade and some speeches beside the Lenin statue. When the photographer called up for a group photo, I just hurried up to stand beside her to catch the moment as well. Intuitively I have also started recording with a video camera and have just recorded around an hour after the group photo. So the group turned into individuals, some go home, some talk to each other, some start to clean up. And the more people leave the square the more pigeons come back and re-enter the square. A child finds a leftover red balloon and starts to play with it and a dog is chasing the pigeons. Live goes on.

A.G.: The book’s layout is in landscape format, just as many of your photos. Why did you often select this format instead of portrait orientation?

T.N.: There are some in portrait orientation, but yes, mainly landscape format. I think in that format it is easier to transport a story. The works of my Japanese Series are all in portrait format despite these are landscape photographs, but they have an abstract concept without any story telling. The Kolyma Series are also landscape photographs but the viewer should feel invited to travel back in history and imagine a story.

T.N.: There are some in portrait orientation, but yes, mainly landscape format. I think in that format it is easier to transport a story. The works of my Japanese Series are all in portrait format despite these are landscape photographs, but they have an abstract concept without any story telling. The Kolyma Series are also landscape photographs but the viewer should feel invited to travel back in history and imagine a story.

A.G.: When I first leafed through the book, before knowing your comments and before reading the texts in the book, several images attracted my attention and questions arose. Is this intended by your mostly brief titles, which only indicate the location of the shot?

T.N.: In a book, I personally prefer when there are many ways to read or to understand it. In my book, there are many different projects and unknown places and maybe it is not easy to follow up. On the other hand, I did not want to explain too much. People can just browse through it or if more interested start to read to get a better understanding.

T.N.: In a book, I personally prefer when there are many ways to read or to understand it. In my book, there are many different projects and unknown places and maybe it is not easy to follow up. On the other hand, I did not want to explain too much. People can just browse through it or if more interested start to read to get a better understanding.

A.G.: Thank you very much for your answers.

Thomas Neumann answered to the questions via e-mail.

All photos ©Thomas Neumann, courtesy of the artist

Thomas Neumann. Exakte Vertrauensgrenzen / Exact Confidence Limits

Fotografie seit 1994 / Photography since 1994

German/English

ISBN 978-3-7757-4759-2

2020

128 pages, 127 images

29,00 x 21,50 cm

bound edition with dust jacket

Hatje Cantz Publishers

40,00 €

Thomas Neumann

Born in 1975 in Cottbus (at this time GDR) Thomas Neumann studied fine arts and photography at the Kunstakademie (Academy of Fine Arts) Düsseldorf in the class of Bernd Becher and Thomas Ruff. Together with other students of Thomas Ruff, he founded the artist group FEHLSTELLE in 2003, which realises art-projects in public space.

His numerous solo exhibitions and group show participations directed Thomas and his artworks in many German cities, but also in other European countries, including some former Eastern bloc countries, Japan, Mexico and Brazil. He published several books on his projects.

Thomas lives and works in Düsseldorf.