Biennale Arte 2019

Biennale Arte 2019

11 May – 24 November 2019

www.labiennale.org

The 58th Venice Biennale is titled “May You Live In Interesting Times”, mistakenly interpreted as a Chinese curse, evoking to the opponent a challenging and menacing life. Ralph Rugoff himself assigned the title not only to artworks, which “reflect upon precarious aspects of existence today”, but has chosen oeuvres including both, “pleasure and critical thinking”*. As result, he curated a wide-ranging main exhibition, where digital art and analogue creations stand side by side, disturbing artworks are opposed to ones, which are only beautifully to look at, or precious gems exist besides noisy eye-catchers.

The Central Pavilion in the Giardini

An example of the last category might be the often in articles quoted industrial robot Kuka. The Chinese artists Sun Yuan and Peng Yu “taught” Kuka 32 different movements to control a thick red liquid to stay within a predetermined area. Reminding Sisyphus, the machine executes its job tirelessly. Besides the impressing technologic spectacle, one could reflect upon monotonous assembly-line work, destruction of work by automation, refusal to be controlled by machines and other concerns of the contemporary world of work and not only.

Almost vulnerable seems to be Alexandra Bircken’s “Angie” nearby. Quasi a classical panel painting on polyester shows the typical gesture of the German chancellor and quietly invites to remind, what is to associate with Angela Merkel. One might think of the refugee crises, open and closed borders or tough stances in the economic crises. Even though other works of the German artist might appear more brachial, like the cut in two racing bike, Bircken recalls our fragility and the need to protect ourselves.

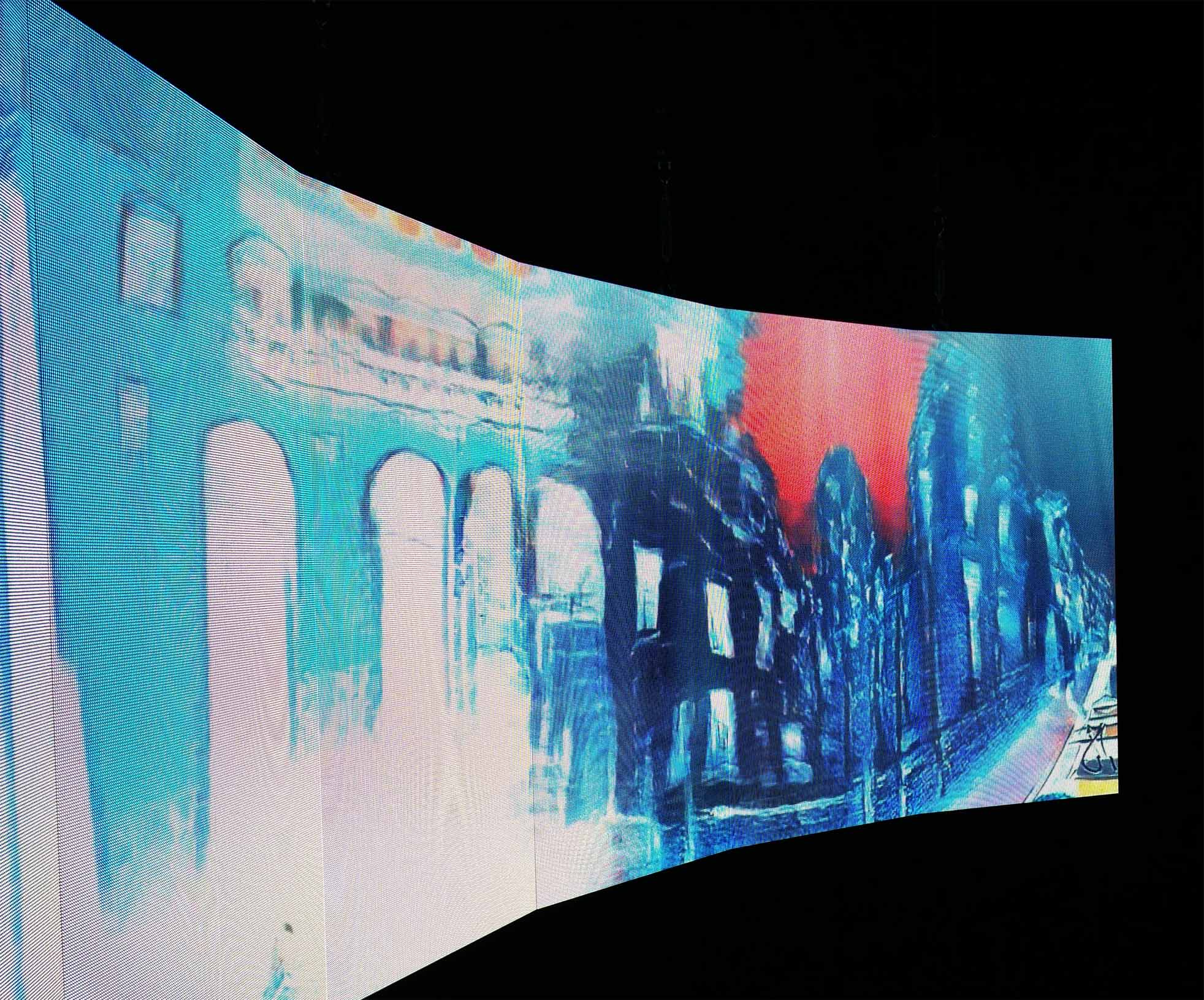

An even more silent witness is “Black Serpentine” by Jimmie Durham. It is a large, mute slab of serpentinite rock in a stainless steel frame. Only the accompanying text describes the history of the stone plate, which starts with the excavation by ‘tribals’ in an Indian quarry, its cutting and processing by underpaid workers and its journey through the Suez Canal, finally arriving in Berlin and Venice.Glances into the past and to the future

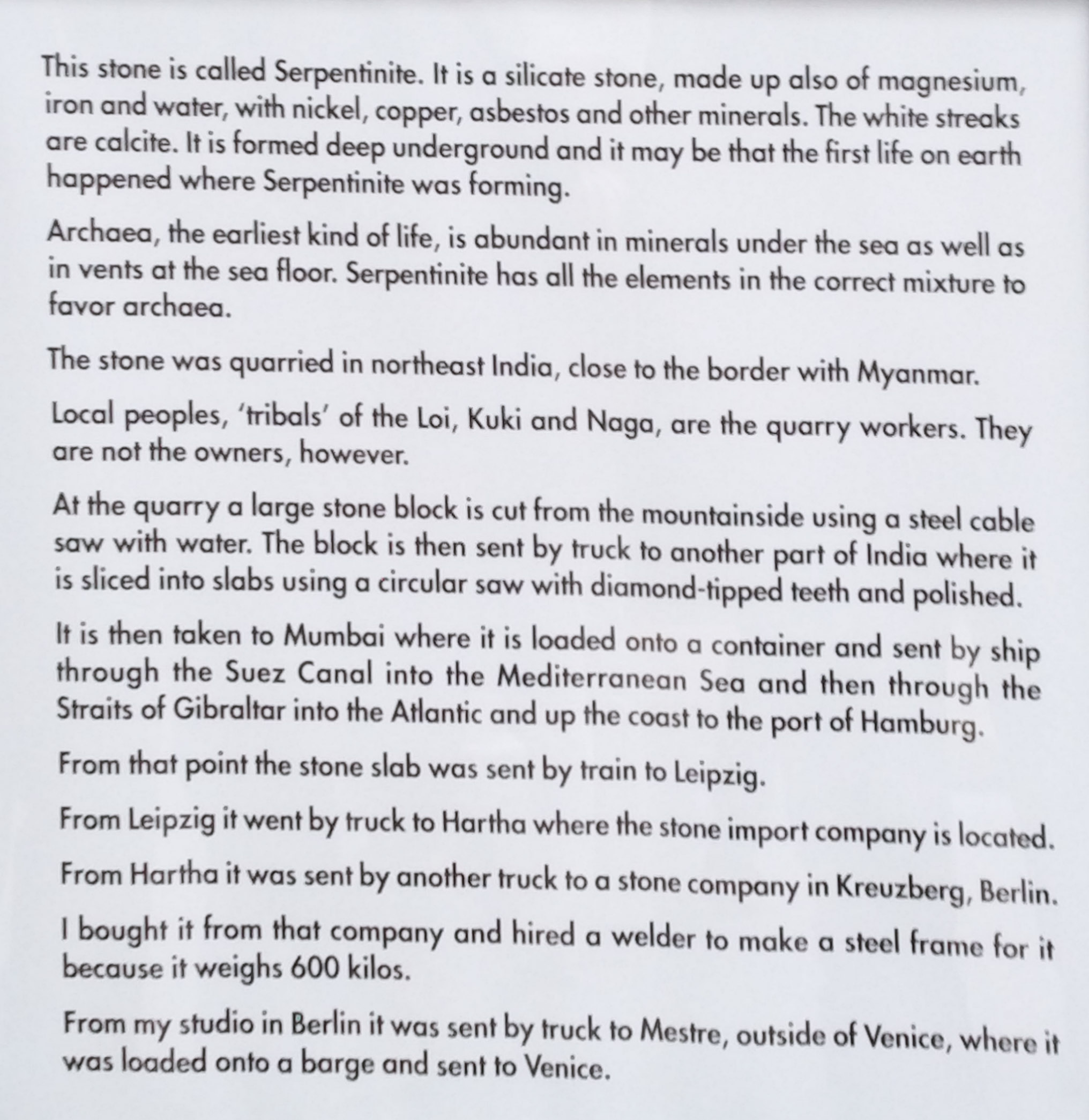

With her three channel video installation “Leonardo’s submarine” the German artist, filmmaker and author Hito Steyerl looks at first sight into the past. The film is about Leonardo da Vinci’s invention of a submarine for the Republic of Venice in 1515. However, the war ship was never build, due to Leonardo’s will to keep it secret. During the projection of coloured underwater shots, the story around it is told. After the passage through drawings from the artist’s sketchbook, there are onshore scenes from Venice. Later the viewer sees war pictures, during which the renaming of the Italian defence contractor in 2017 from “Finmeccanica” into “Leonardo” is explained. The enterprise supplied Turkey with weapons used against civilians in Syria. Herewith Steyerl denounces the practice of “artwashing”. Finally, a predictive algorithm renders the video into the future to look out for other, until now, undiscovered inventions of Leonardo. Found was the instruction to hinder weapon manufacturers to approach by using artificial shrieking sounds. It turns out that the visitor is sitting inside the demanded simulator. With her impressive noisy installation, Steyerl wanders from the past into the future through our present, reflecting on war, its weapons and its impacts. Additionally, she creates references to the exhibition site, contemporary challenges and refers to the 500th death anniversary of the polymath Leonardo da Vinci.

The time range in the work of the Ukrainian artist Zhanna Kadyrova is smaller and less eye-catching. Nevertheless, her clothes made of ceramic tiles are not only interesting designed garments, but also contain history. For the Venetian part of “Second Hand”, she used tiles from a hotel in town. Moreover, she refers to her home country, which has a long history of ceramic tile production. In previous parts of the project, Kadyrova transformed tiles from former Soviet-era industrial buildings. Herewith, she pointed to the country’s Soviet past, before all traces of it were erased, due to the Russian-Ukrainian conflict. Calm and motionless as the dead appears Jean-Luc Moulène’s sculpture “La Faucheuse” (The Grim Reaper). It is a simple installation of a scythe attached to a blue plastic chair. It might be a reminder to the finality of life or the emptiness, which spreads in one’s mind after the loss of a beloved being. On the other hand, the vibrant blue of the chair emit some kind of dynamic, as if the invisible pale death is sitting there, waiting to catch the next bystander.

Calm and motionless as the dead appears Jean-Luc Moulène’s sculpture “La Faucheuse” (The Grim Reaper). It is a simple installation of a scythe attached to a blue plastic chair. It might be a reminder to the finality of life or the emptiness, which spreads in one’s mind after the loss of a beloved being. On the other hand, the vibrant blue of the chair emit some kind of dynamic, as if the invisible pale death is sitting there, waiting to catch the next bystander.

The main exhibition in the Arsenale

In the Arsenale, there are several artists, also represented in the part of the main exhibition in the Giardini. Hito Steyerl contributes another video installation “This is the Future”, were she reflects on the possibility to predict the future and the role artificial intelligence might play in our lives. Zhanna Kadyrova installed a “Market”. However, the offered food is made out of concrete and stone. Moreover, Alexandra Bircken added three further oeuvres. Other artists, not mentioned yet, were on view in both venues.

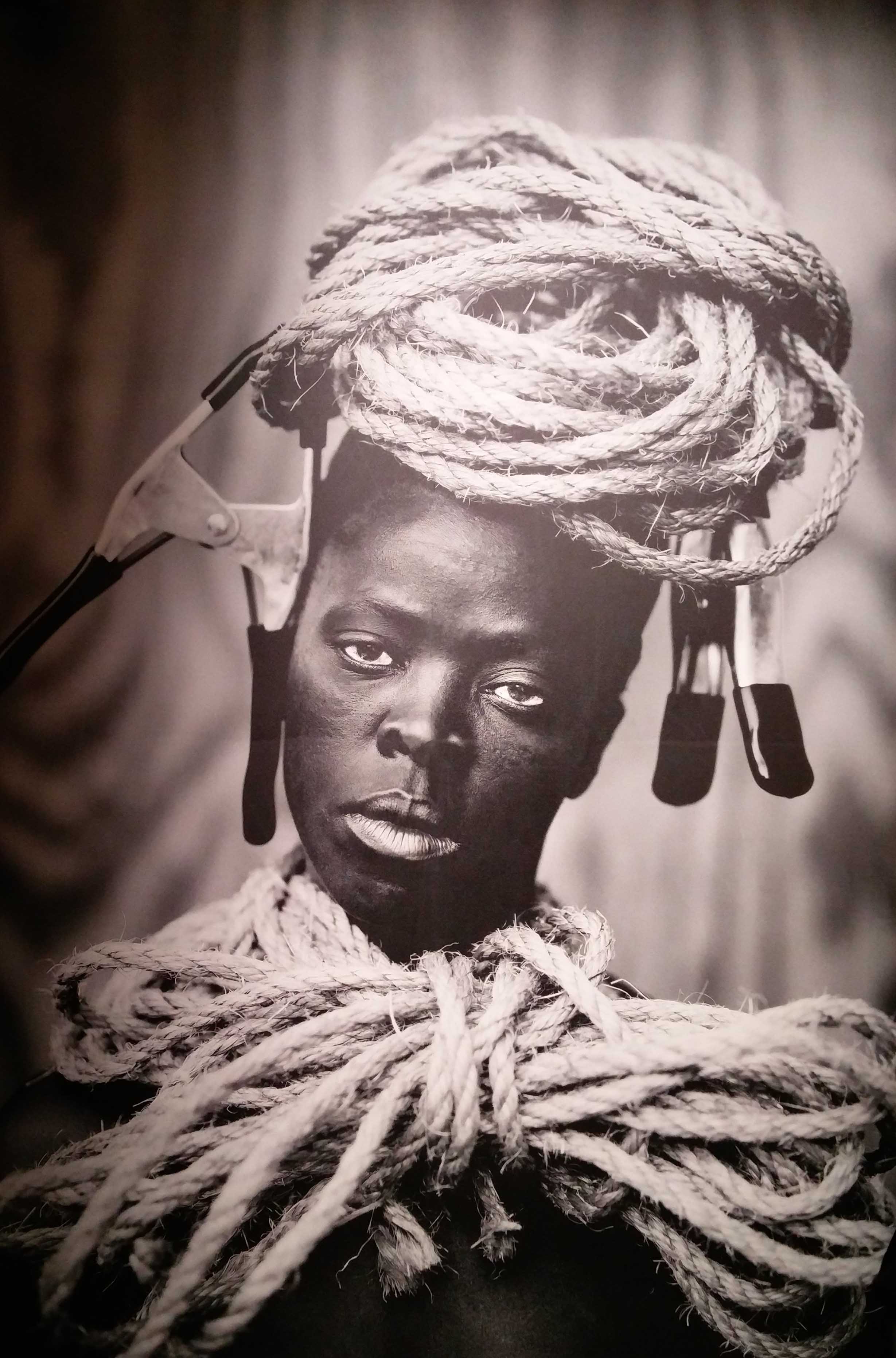

Relatively at the beginning, there are two huge wallpapers by Zanele Muholi. The South African “visual activist” shows photos of her series “Sonyama Ngonyama, Hail the Dark Lioness”. The pictures are self-portraits, which recall at first glance aesthetically colonial depictions. Nevertheless, on closer inspection they are disturbing, since she uses uncommon elements as costume. In “MaID III, Philadelphia”, the artist wears a necklace and headdress made from a rope. The cord around the neck is laced as if bearing a pulling down load. Laterally attached to the turban are big clamps, like instruments of torture. Another photo of the series, “Namhla at Cassilhaus, Chapel Hill, North Carolina”, on view in the Central Pavilion, gives a similar impression. “Destination” by the Chinese artist Nabuqi is seems to be an invitation into the beautiful idyll of the Caribbean. It is an inclined positioned billboard. Depicted is a photo of white sand, turquoise sea and blue sky with palm tree. In one place, there is even an artificial palm growing out of the white sand through the image. A perfect scene that could be used as advertisement for dream holidays. However, turning around the installation and looking under the perfect paradise, one could see a group of artificial plants as to unmask the fake.

“Destination” by the Chinese artist Nabuqi is seems to be an invitation into the beautiful idyll of the Caribbean. It is an inclined positioned billboard. Depicted is a photo of white sand, turquoise sea and blue sky with palm tree. In one place, there is even an artificial palm growing out of the white sand through the image. A perfect scene that could be used as advertisement for dream holidays. However, turning around the installation and looking under the perfect paradise, one could see a group of artificial plants as to unmask the fake.

Between security and presssure

Additionally, the utopic scene is disturbed by a whipping noise from time to time. Going further, one discovers another installation (Dear) by the Chinese artist duo Sun Yuan and Peng Yu as source of the sound. A rubber hose, attached to a white chair whips violently around the surrounding space. After several seconds, the eruption of violence is over and the visitor can appreciate the white silicon chair behind Plexiglas. The throne recalls the imperial Roman chair, where Abraham Lincoln is sitting on, in his Washington Memorial. Though the ornamental Roman fasces, symbol for governmental authority are replaced by simple semicircle pillars. The president of the American Civil War and the abolition of slavery left his chair and the periodically erupting, aggressive rubber hose takes his position. Is it a symbol for state violence?

Another representation of oppression are the black-and-white photo series “The Wall”, “The Wall at Night” and “Gates to Heaven” by the Palestinian artist Rula Halawani. In a photo-journalistic manner, they illustrate the wall and its gates, built by Israel to control the access to Israel and the occupied territories. For Palestinian people the wall is a symbol of the imposed pressure and the fragmentation of their land. Whereas for the Israeli it is a security barrier. Besides the specific context given by the artist, the photos recall other border fortifications like the overcome Berlin Wall or the existing fence systems at the external European borders and the planned wall between Mexico and the United States. With “Chair for the Invigilator” the Lithuanian artist Augustas Serapinas wants to create alternative points of view, but could also be interpreted as a questioning about security and surveillance. Inspired by the elevated chairs of lifeguards in bathing areas, they stand for security. On the other hand, the chairs are designated for the exhibition’s mediators, who can survey the audience below. Often invisible in the crowd, they are highlighted, which might help people to locate them in case of any need. However, the raised position might create a distance to the audience and hinder people to address the mediators. Moreover, the chairs could recall watchtowers at border fortifications and prisons. Here the decision between security and surveillance or imprisoning and exclusion is also ambiguous, depending of the point of view.Enlargements and insights to the human body and soul

Also “Microworld” by Liu Wei changes the perspective of the spectator. Evoking the glance at a greatly enlarged universe, the Chinese artist presents collections of huge geometric shapes out of highly-polished aluminium. The curved forms are arranged dense adjoin and above each other and take up almost the entire room. This imaginary depiction of a microscopic attract the onlooker like an unknown world. Nevertheless, this cosmos remains inaccessible due to a giant window, another hint to the look through a microscope.

Also “Microworld” by Liu Wei changes the perspective of the spectator. Evoking the glance at a greatly enlarged universe, the Chinese artist presents collections of huge geometric shapes out of highly-polished aluminium. The curved forms are arranged dense adjoin and above each other and take up almost the entire room. This imaginary depiction of a microscopic attract the onlooker like an unknown world. Nevertheless, this cosmos remains inaccessible due to a giant window, another hint to the look through a microscope.

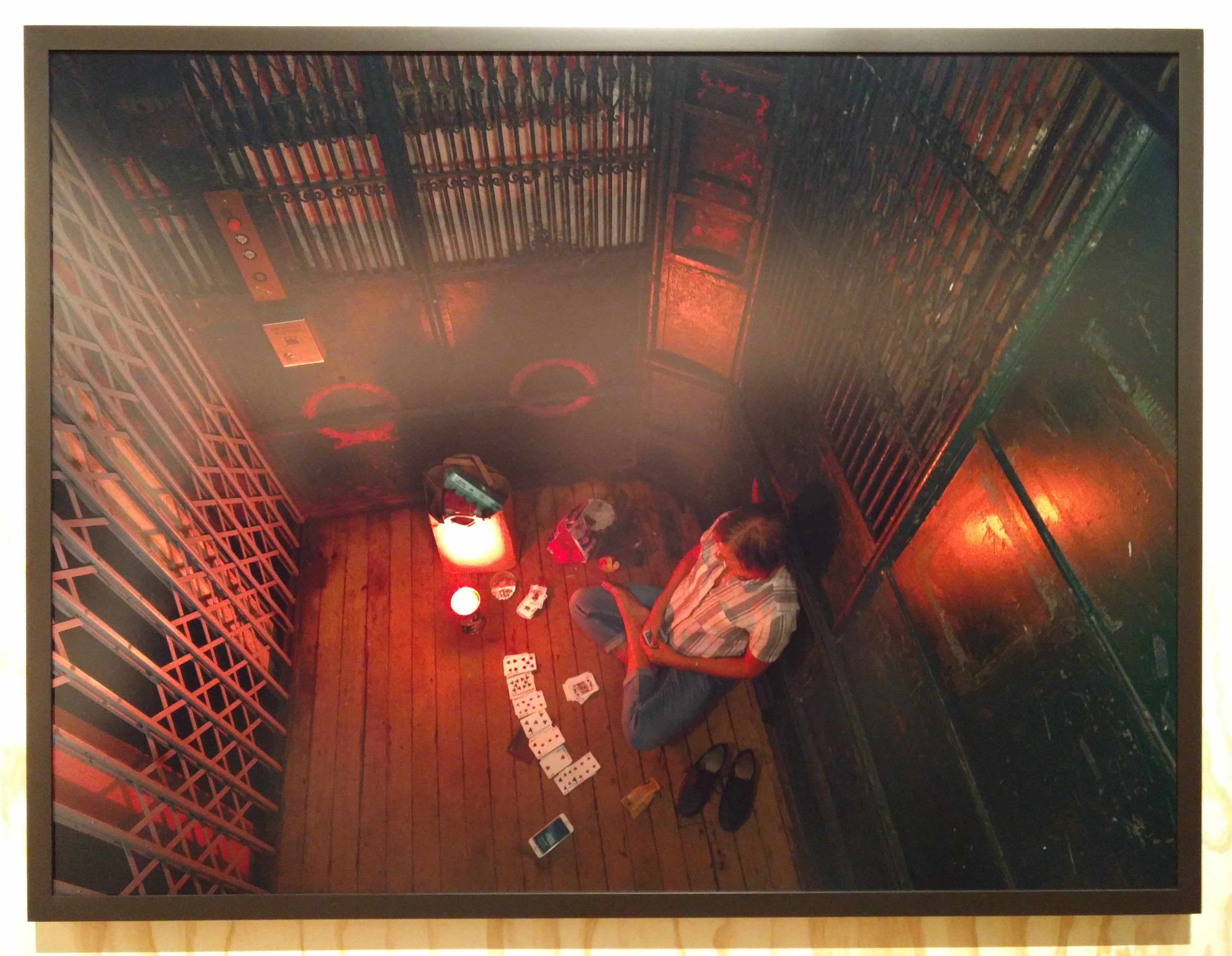

Stan Douglas takes us with his photo series to another, more real dramatic world. With “Scenes from the Blackout”, the Canadian artist imagines what the impact of a total loss of electric power might have. It could lead to inventiveness like in the photo “Solitaire”. Trapped in an elevator, a woman makes a candle out of vegetable fat. However, the uncommon situation could lead also to disinhibition of people as looting and theft. Douglas’ series functions like a photo story or a film without movement. The photos accentuate not only the fragility of our lifestyle, but in parallel, they make aware that the human condition is instable and might change abruptly.

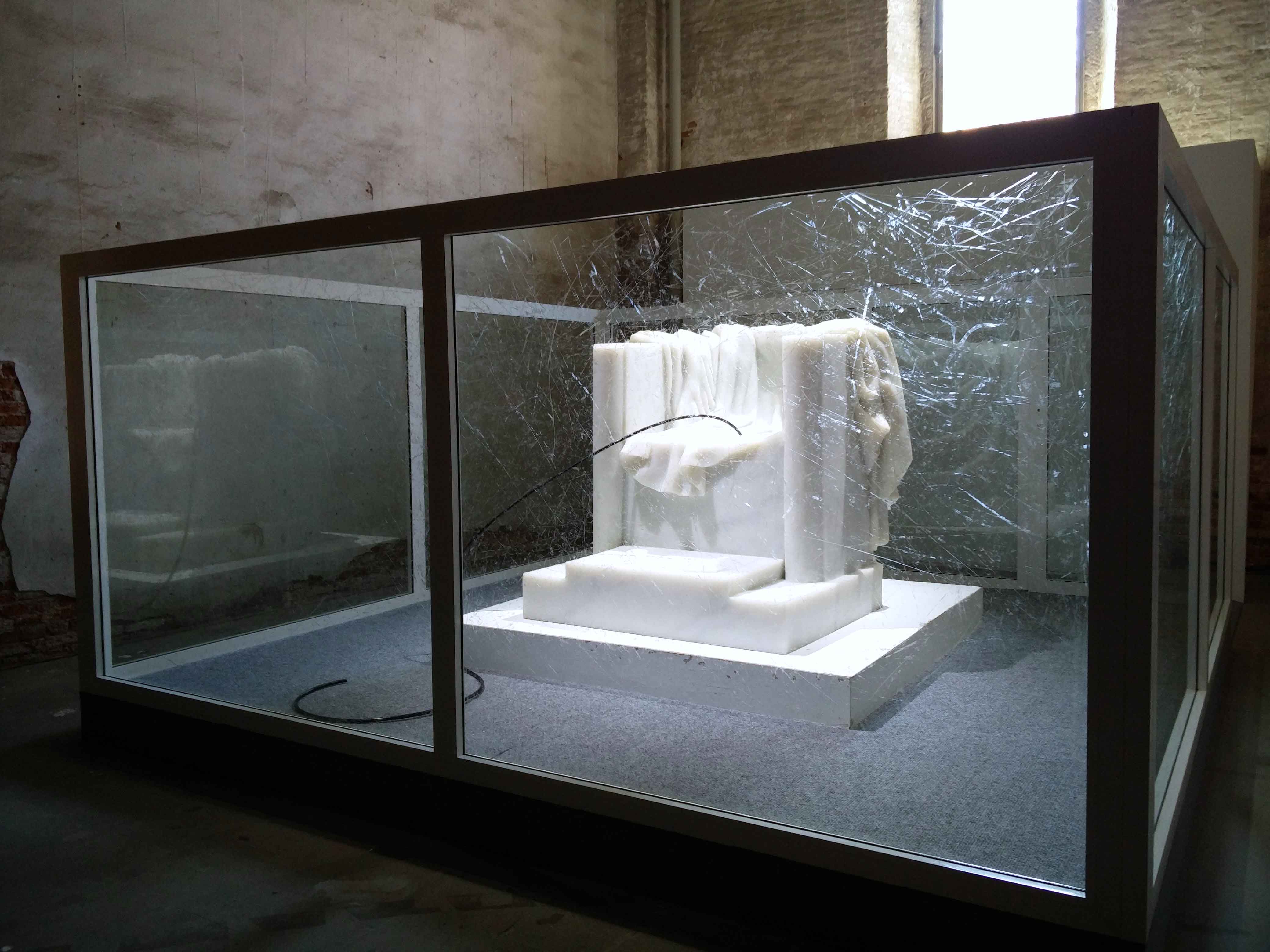

Like a river, Otobong Nkanga’s “Veins Aligned” meanders 26 metres through one of the huge halls of the Arsenale. By the title, the sculpture made from marble and glass, seems to be an oversized blood vessel recalling Liu Wei’s “Microwold”. However, the angular form contrast with the curved shapes of the Chinese artist. Moreover, the form and the material does not match with the soft blood supply line in the human or animal body. This ambiguity should be intended by the Nigerian artist, who “described landscape as body, which nourishes and provides”. Additionally, the choice of the material refers to the colonial and post-colonial exploitation of natural resources, extracted from the body of the earth.

Like a river, Otobong Nkanga’s “Veins Aligned” meanders 26 metres through one of the huge halls of the Arsenale. By the title, the sculpture made from marble and glass, seems to be an oversized blood vessel recalling Liu Wei’s “Microwold”. However, the angular form contrast with the curved shapes of the Chinese artist. Moreover, the form and the material does not match with the soft blood supply line in the human or animal body. This ambiguity should be intended by the Nigerian artist, who “described landscape as body, which nourishes and provides”. Additionally, the choice of the material refers to the colonial and post-colonial exploitation of natural resources, extracted from the body of the earth. By its skin colour, Carol Bove’s sculpture “Bather” recalls as well the human body. It could almost be a softened folded version of Nkanga’s. However, by its visible materiality “Bather” seems to be lighter than the marble vein, even though, it is made from stainless steel. Due to the size, the onlooker needs to turn around the sculpture to capture it completely. Moreover, “Bather” invites by its radiance to be touched, which is understandably forbidden in the exhibition. Still, it is nice to look at. By the way, there are more sculptures by the American artist in the Central Pavilion, often in bright colours.

By its skin colour, Carol Bove’s sculpture “Bather” recalls as well the human body. It could almost be a softened folded version of Nkanga’s. However, by its visible materiality “Bather” seems to be lighter than the marble vein, even though, it is made from stainless steel. Due to the size, the onlooker needs to turn around the sculpture to capture it completely. Moreover, “Bather” invites by its radiance to be touched, which is understandably forbidden in the exhibition. Still, it is nice to look at. By the way, there are more sculptures by the American artist in the Central Pavilion, often in bright colours.

There are many more attracting artworks in the main exhibition that cannot all be mentioned. Often it is recommendable to read the texts and take some time in front of the oeuvres. This could often reveal much more than only a short glance. Overall, we passed an interesting time at the 58th Biennale di Venezia.

* https://www.labiennale.org/en/art/2019/58th-exhibition

If not otherwise mentioned, the quotes are from the Biennale Short Guide: May You Live In Interesting Times. First Edition, May 2019

Text: Astrid Gallinat

Photos © Astrid Gallinat & Stephan Goseberg, if not mentioned otherwise